Algorithmic Governance, Institutional Gaps, and Political Control in Central Asia

Evidence from a 2025 national survey experiment in Kazakhstan on when citizens support—and even welcome—algorithmic governance tools.

Understanding Support for Algorithmic Governance in Autocracies

Michael Rochlitz (website) and I extend our earlier research on digital governance — most recently in our Comparative Political Studies article on public support for governance systems powered by AI (link) — to explore where the “entry points” for technology acceptance lie in autocracies, and how people weigh efficiency and convenience against the risks of surveillance and political control.

Algorithmic governance systems (AGS) — such as facial recognition, automated decision-making, digital monitoring, and large-scale data integration — are rapidly spreading across developing and authoritarian states. Kazakhstan, a key hub in China’s Digital Silk Road, is one of the earliest adopters.

AGS offer a dual promise:

- Governance benefits: reduced corruption, more efficient public services, faster bureaucracy

- Political risks: expanded surveillance, limits on civic freedoms, and tools for targeted repression

To understand how citizens evaluate these trade-offs, we conducted a nationally matched online survey experiment (N = 3,124) in March 2025 in Kazakhstan.

Our central question:

When do citizens welcome algorithmic governance — and when do they fear it as a tool of political control?

Experimental Design: A 2×6 Factorial Structure

We implemented a 2 × 6 experiment, crossing six message framings with an orthogonal repression cue.

Schematic Overview of Experimental Conditions

| Message Type | No Repression | + Repression Cue |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional gap | Corruption | Corruption + Repression |

| Institutional gap | Radicalization | Radicalization + Repression |

| Institutional gap | Security | Security + Repression |

| Institutional gap | Trust | Trust + Repression |

| Institutional gap | Epidemics | Epidemics + Repression |

| None | Control | Repression + Control |

| Total Conditions | 12 Treatment Arms (2 × 6) | |

This design allows us to estimate:

- How different institutional gaps affect support for AGS

- How repression cues reshape attitudes, and

- Which groups welcome or resist algorithmic repression

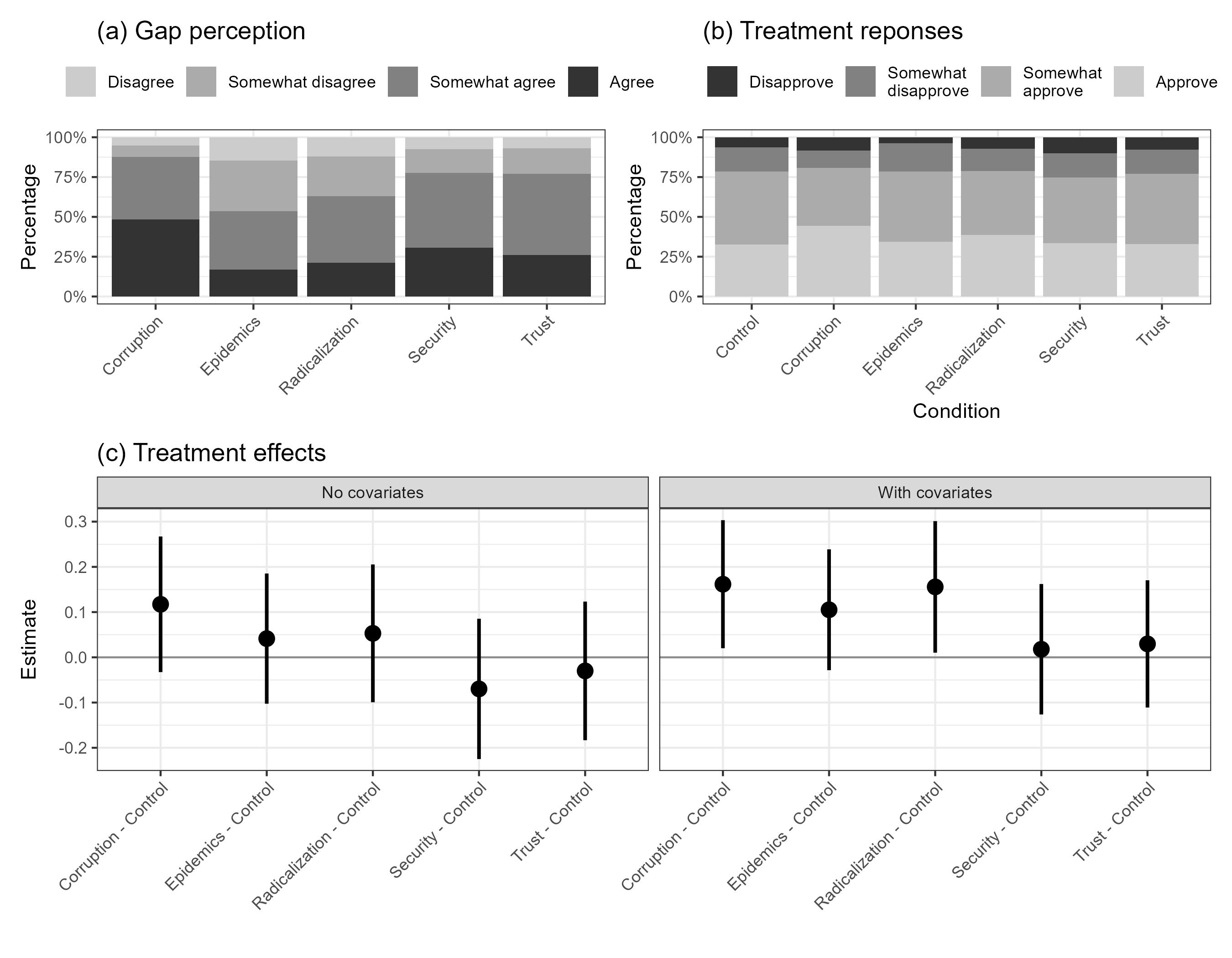

1. Institutional Gaps in Kazakhstan

The first step is understanding which problems citizens perceive as most severe.

Key insights:

- Corruption dominates public concern — nearly 90% see it as a major problem.

- Security and trust gaps are also salient.

- Epidemics and radicalization still matter, but less intensely.

Despite this variation, support for AGS is extremely high across all framings:

even in the pure control group, 78% approve.

This baseline support resembles levels in China and exceeds those in Russia, Eastern Europe, and OECD democracies.

2. Do Institutional Gaps Increase Support for AGS?

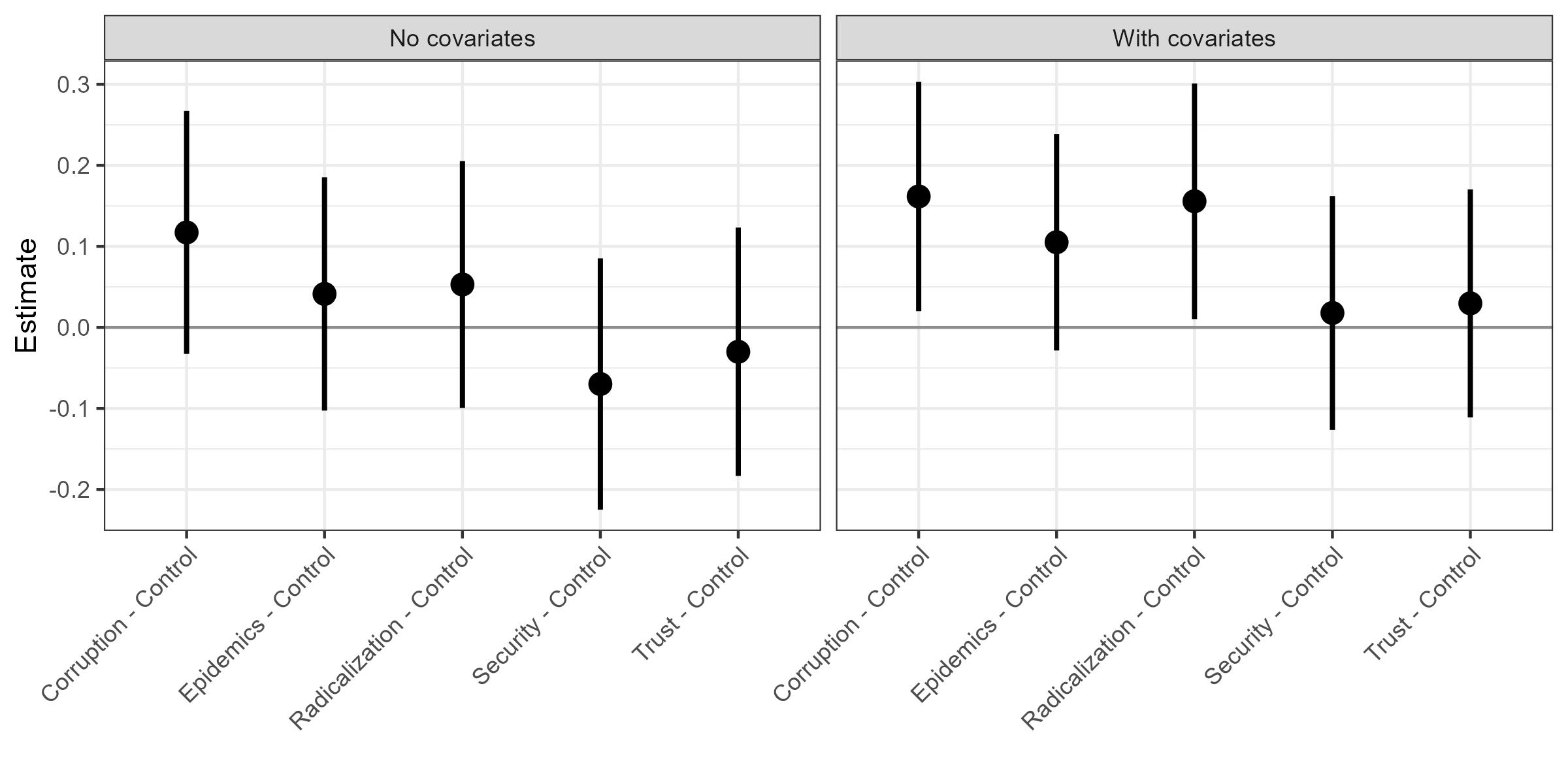

We next estimate average treatment effects (ATEs) of each institutional-gap framing relative to the control.

What do we learn?

- Corruption and radicalization framings generate the strongest increases in support.

- Other gaps (security, trust, epidemics) generate little or no average effect.

- All effects are modest because baseline support is already extremely high.

Still, citizens clearly see AGS as particularly appropriate for addressing corruption and extremism — two politically sensitive issues in Kazakhstan.

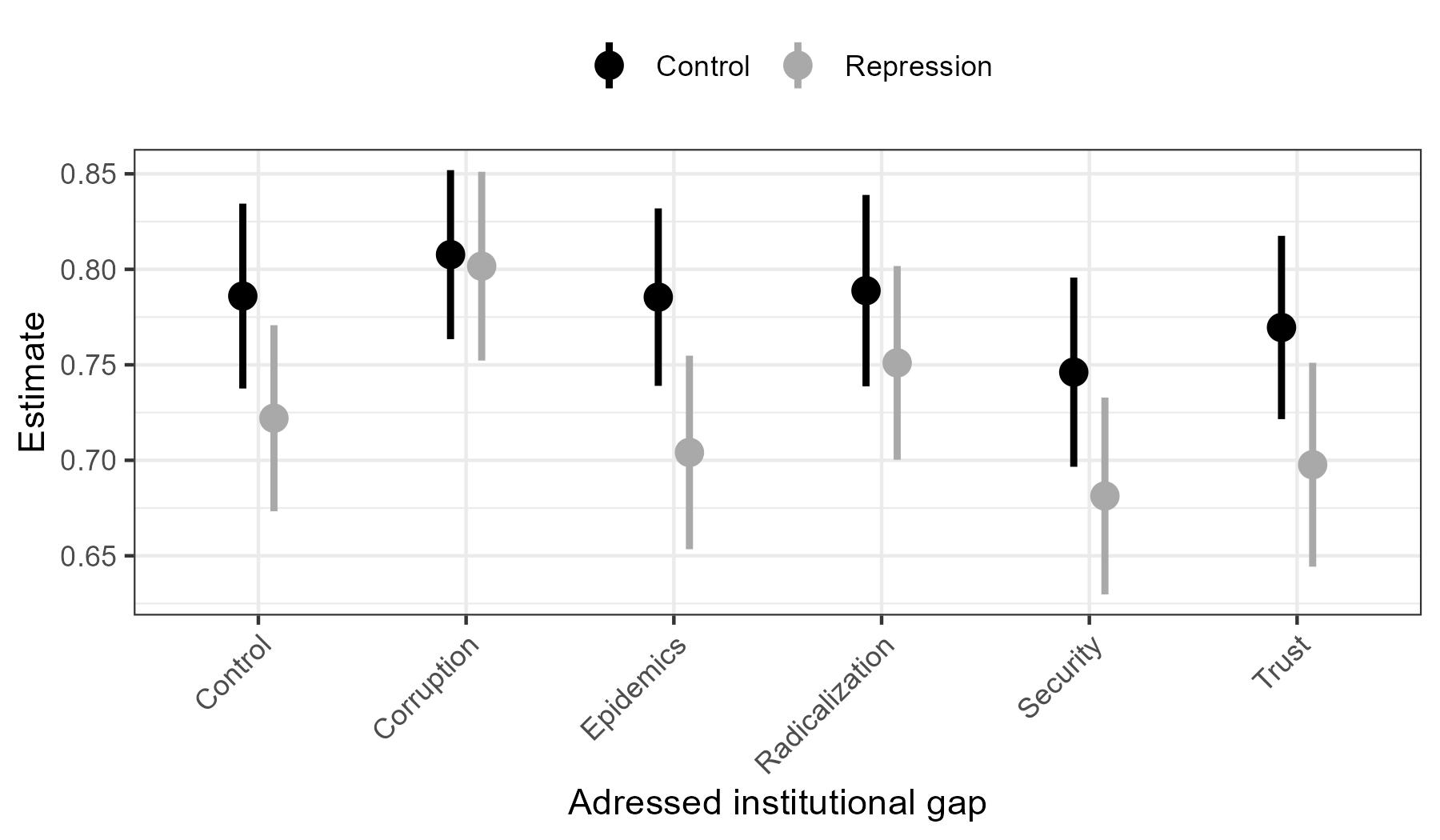

3. The Repression Cue: A Limited but Meaningful Backlash

We now introduce the key tension:

How do citizens react when reminded that AGS can be used against protesters or journalists?

Findings:

- Repression reduces support by 5.9 percentage points on average.

- This shows that even in a semi-authoritarian context, many citizens value civic freedoms.

- Yet the decline is far smaller than the 24-point drop we observed in Russia (2022).

Importantly, repression does not reduce support uniformly across all groups or framings.

For some combinations, repression increases support — a striking deviation from standard political-economy models.

This leads us to the final section.

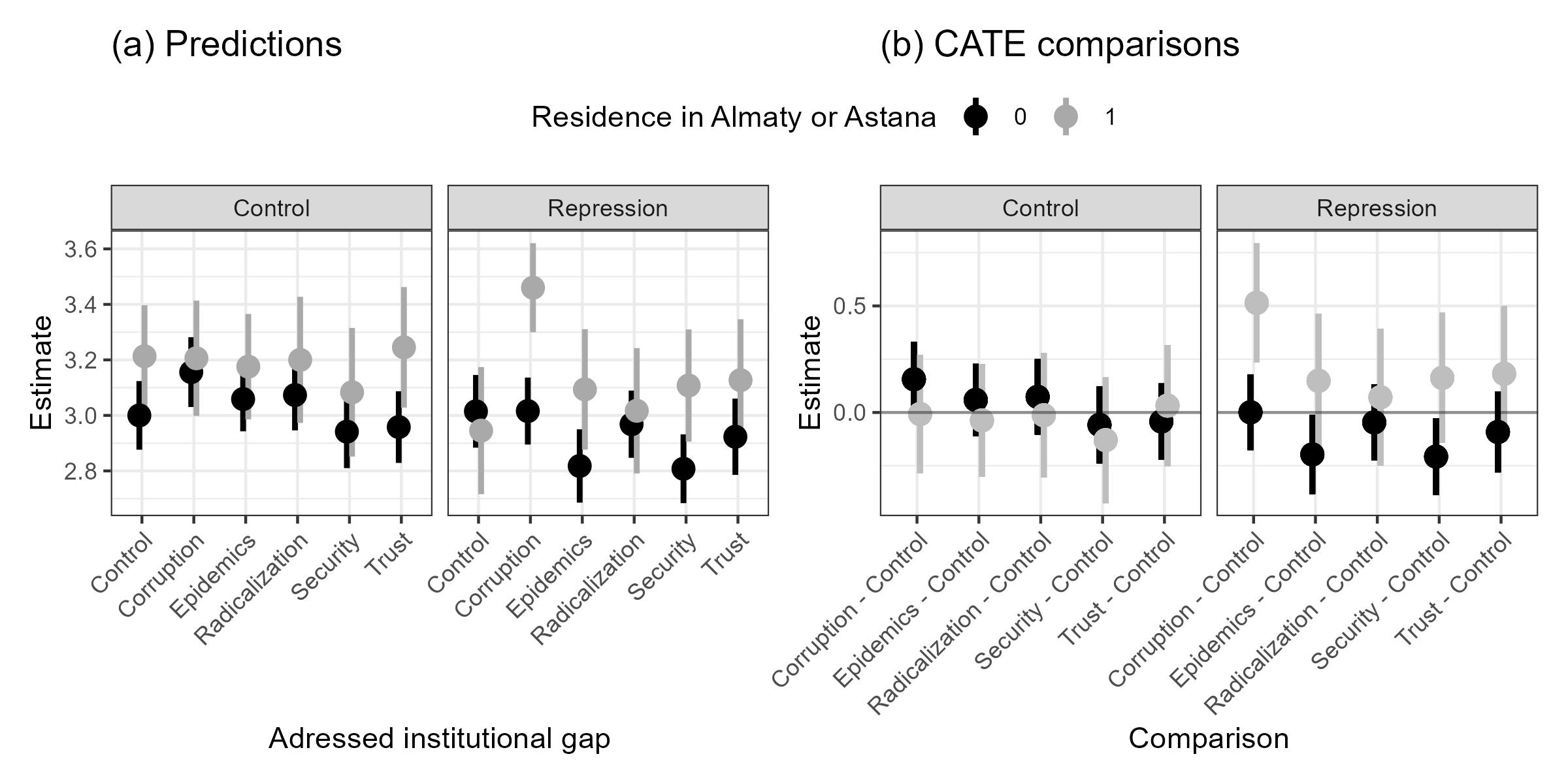

4. Heterogeneous Effects: When Do People Welcome Repression?

One of the most surprising results is that certain groups increase their support for AGS when repression is made explicit.

The clearest example involves residents of Kazakhstan’s two largest cities:

It appears that corruption is such a serious problem (recall the first figure at the beginning) that citizens are eager to give the state more power to address it.

More than that, they increase their support even further when the state is able to use repression — but only when repression is presented together with efforts to combat corruption.

Key takeaways:

- Urban residents (Almaty & Astana) show the highest baseline support.

- When corruption is paired with repression, support increases dramatically — by about 0.5 points on a 4-point scale.

- This is a surprisingly large effect.

Across additional subgroups (not shown here):

- Russian-speakers reject repression in most domains —

except when repression targets corruption, which they strongly support. - Religious respondents show increased support when repression is tied to counter-extremism.

- High-trust individuals remain supportive irrespective of repression cues.

Interpretation:

For some citizens, repression is not a cost of AGS —

it is a feature.

This complicates the standard assumption that repression uniformly reduces support for digital governance tools.

Conclusion

This study provides the first experimental evidence on how institutional-gap framings and repression cues shape support for algorithmic governance in a Central Asian autocracy.

Main findings:

- Baseline support for AGS is extremely high (78%).

- Corruption is the strongest institutional rationale for AGS adoption.

- Repression cues reduce support, but only slightly.

- Some groups welcome algorithmic repression when it targets perceived societal “threats.”

These results challenge the conventional repression–legitimacy trade-off model.

In Kazakhstan, support for digital governance does not always decline when authoritarian risks are highlighted.

Under certain conditions, algorithmic repression becomes politically acceptable — even desirable.

We are now conducting follow-up qualitative interviews in Almaty, Astana, and across the country.

More results soon.