We Asked Americans About Government Surveillance in 2022. Now It's Happening.

In late 2022, Michael Rochlitz and I ran a survey experiment asking Americans about their support for a hypothetical digital governance system. The scenario we described was straightforward. A government platform that combines data from multiple sources (facial recognition, video surveillance, government databases) to identify and prosecute people who “violate law and order.” In one treatment condition, we specifically told respondents that this system could be used to identify people who “participated in an unauthorized political protest.”

That hypothetical scenario is now reality. ICE agents are using a face recognition app to scan the faces of people in the field. They are pulling health records from Medicaid data on 79 million Americans to decide where to conduct raids. They are using location data to track protesters. What we designed as an experimental treatment has unfortunately become policy in the US.

When data is used to repress political protest, privacy becomes less a question of consumer protection and more a question of citizen protection, a condition for democratic participation. Privacy is not primarily an ethical question. It is a political one.

Who Supported Protest Surveillance in 2022?

We surveyed 1,000 Americans as part of a five-country study. Among respondents who were told explicitly that the system could track political protesters, about 41% approved. This was already the lowest approval rate among all countries we studied.

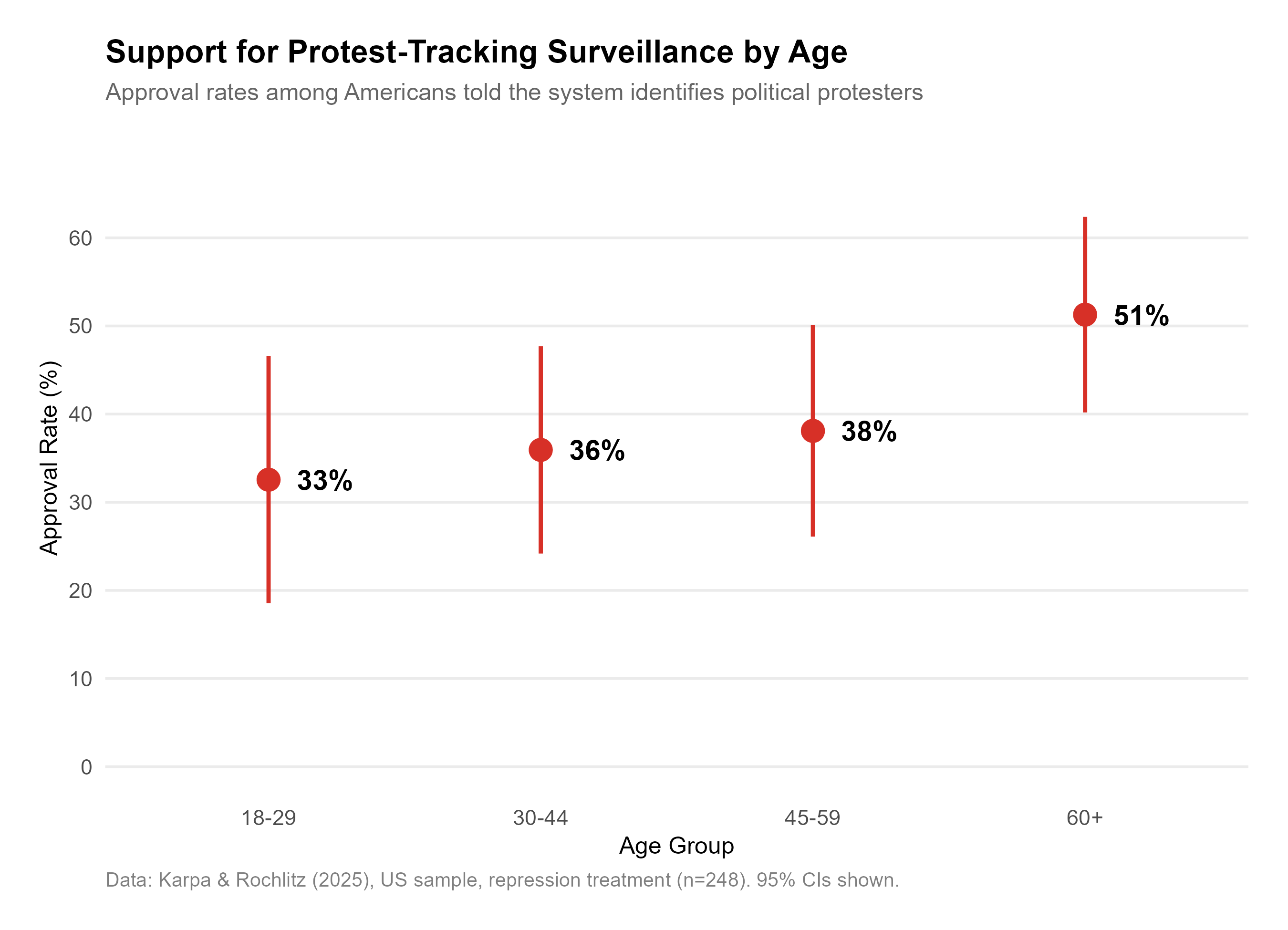

But support was not uniform. The clearest divide was generational.

Only 33% of young Americans (ages 18-29) supported the system when told it could identify protesters. Among those over 60, support jumped to 51%.

This isn’t surprising when you consider who participates in political protests. Young Americans who came of age during the Black Lives Matter protests, climate strikes, and various social movements likely see themselves as potential targets. Older Americans apparently less so.

The Partisan Divide

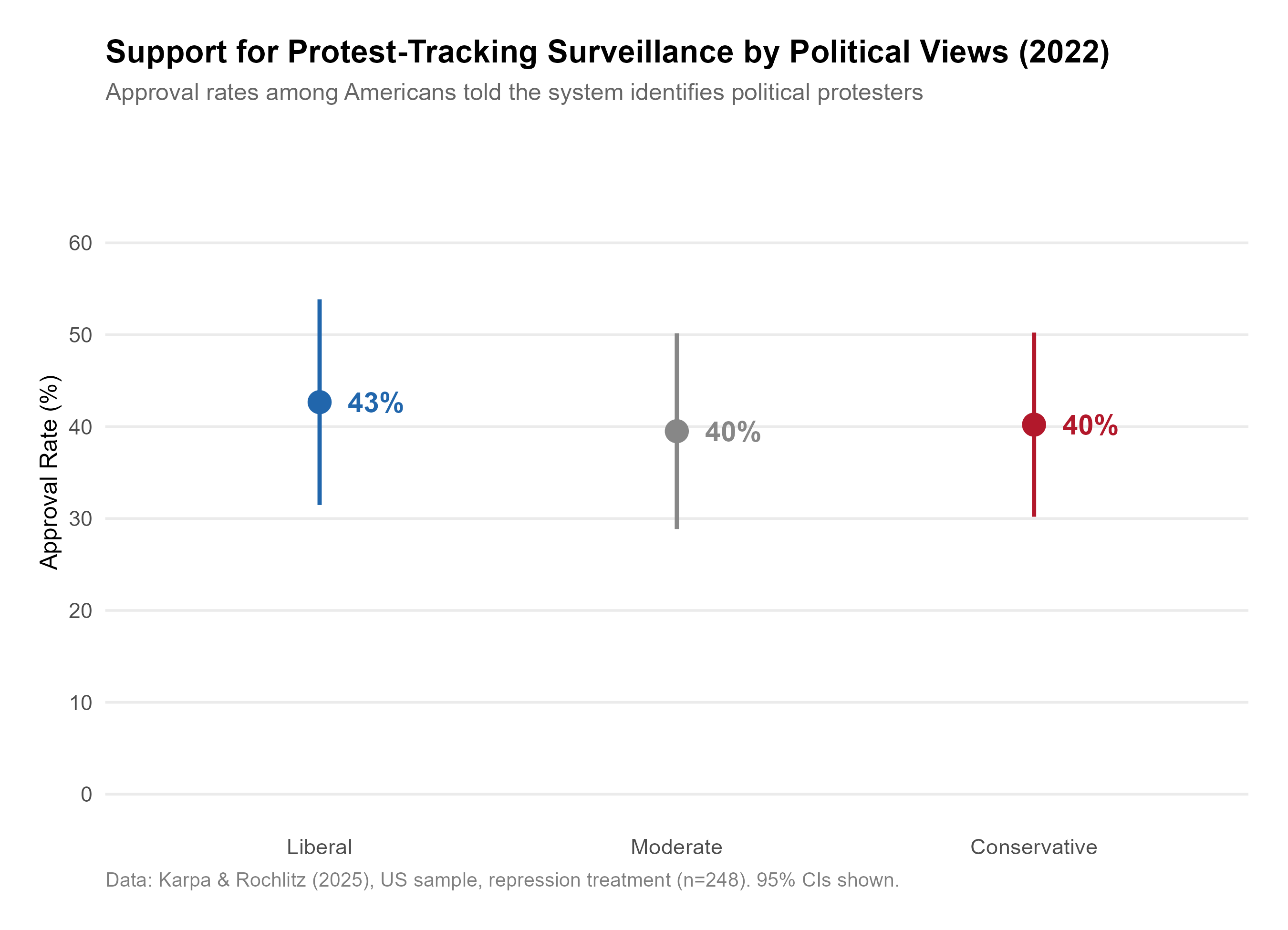

In our 2022 survey data, the partisan divide on protest surveillance was surprisingly small. Liberals, moderates, and conservatives all showed similar levels of support, around 40%.

Why? In our 2022 data, liberals actually showed slightly higher support for protest-tracking surveillance than conservatives (43% vs 40%). This is counterintuitive until you consider that the question asked about a system to track “unauthorized” protests. Democrats may have been thinking about January 6th; Republicans may have been thinking about Black Lives Matter.

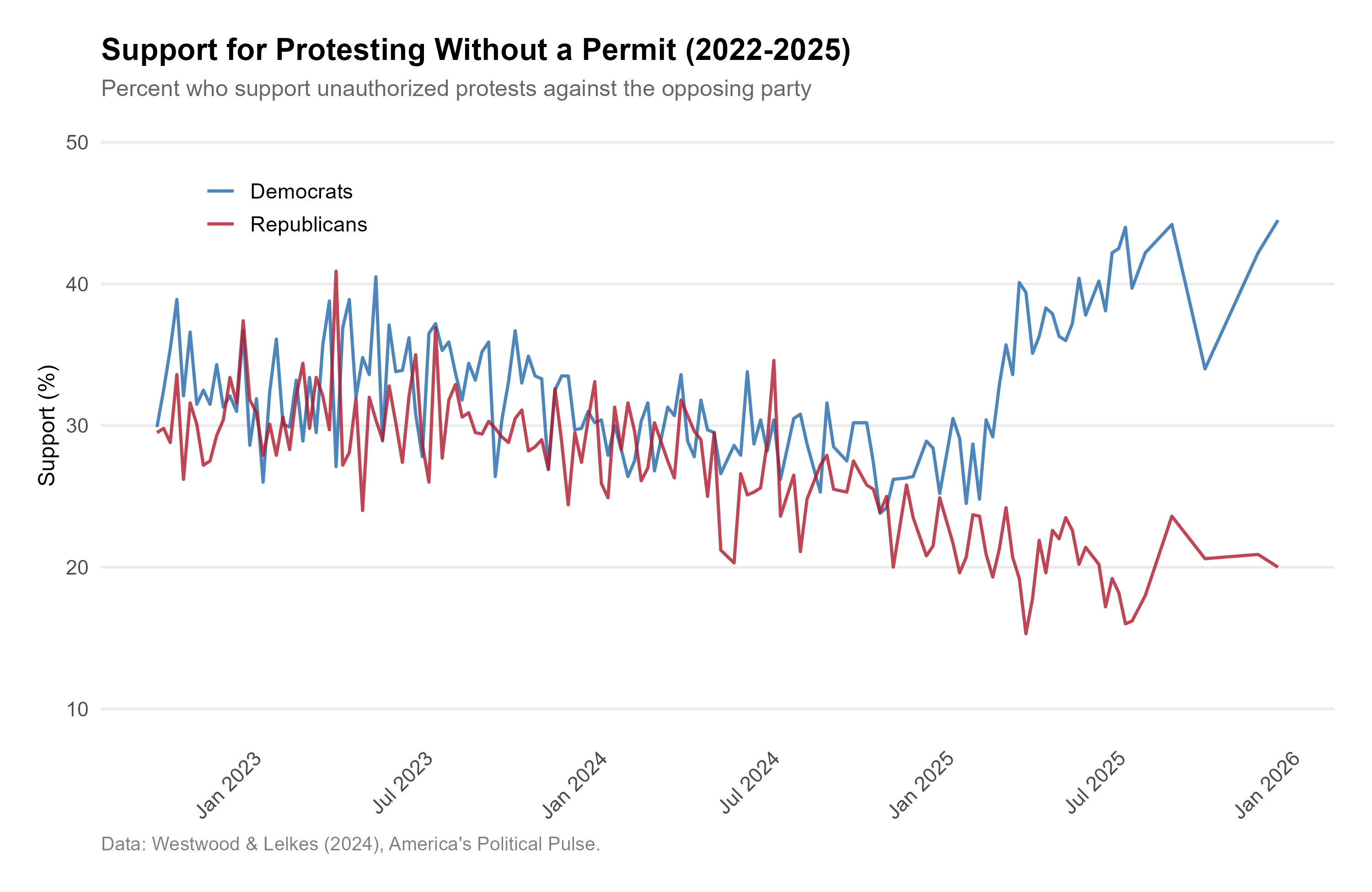

Data from America’s Political Pulse (Westwood & Lelkes, 2024) on a related question shows how views on protest have diverged since 2022.

When asked whether they support someone protesting without a permit against the opposing party, Democrats and Republicans were nearly identical in late 2022, both around 30%. By late 2025, Democrats had risen to over 40% while Republicans dropped below 20%. Democrats have become more supportive of protest as a political tool; Republicans less so.

The Ratchet Effect

In our paper published in Comparative Political Studies, we discuss what we call the technological “ratchet effect.” Once surveillance infrastructure is built, it can become difficult to dismantle. The facial recognition databases, data-sharing agreements, and AI systems being deployed today may outlast any particular administration.

We are seeing this play out in real time. Through the 2025 domestic policy bill, Congress allocated $75 billion to ICE alone, making it the highest-funded federal law enforcement agency in the country. This money is available until September 2029, with no reporting requirements and no restrictions on how it can be spent. Even a government shutdown would not stop ICE operations because the funds have already been allocated.

Meanwhile, DOGE employees have been accessing sensitive personal data at the Social Security Administration and sharing it on unsecured cloud servers. The data includes birth certificates, parents’ names, and other information that can be used for identity theft or, as one DOGE employee allegedly intended, to “find evidence of voter fraud and to overturn election results.”

This is one way the ratchet effect operates. Once data has been collected and shared, you cannot make someone un-have it. Once databases are connected and contractors like Palantir have access, it is too late. ICE is now using a Palantir app called “Elite” that pulls health records, addresses, and photos from Medicaid data on 79 million Americans to decide where to conduct raids.

Beyond Palantir, ICE has purchased tools called Tangles and Webloc to monitor social media activity and track cell phone locations. The location data comes not from telecom companies, which would require a warrant, but from the advertising ecosystem. When an ad loads in an app, location data is harvested and sold to government contractors. Users can draw a circle around a protest location and track where those phones go afterward. This practice is well-established. Byron Tau documented it in his 2024 book Means of Control, showing how intelligence agencies circumvent domestic spying restrictions by purchasing “publicly available” data from advertising exchanges.

In hybrid regimes and countries that swing between more and less authoritarian forms of government, a well-functioning surveillance infrastructure plays the role of a technological ratchet. It can permit a country to switch from softer to harder authoritarianism and make it harder to switch back and democratize again by repressing and intimidating protesters.

Privacy Is Political

Privacy debates are usually framed in ethical terms. Is it right to collect this data? Do people have a reasonable expectation of privacy? These are important questions, but they miss a point.

When governments use health records, advertising data, and social media to track protesters, privacy can become a political question. When ICE uses location data to identify who attended a protest and where they live, privacy is no longer only about individual dignity or consumer rights. It can become about whether democratic opposition can be voiced without repercussions.

The ratchet effect makes this concrete. Once the infrastructure exists, once the databases are connected, once Palantir and the advertising brokers have access, the data cannot be un-collected. The surveillance apparatus may be available to whoever holds power next, and could be used against whoever opposes them. This is why categorical limits on data collection matter so much, and why exemptions can hurt democracy over time.

Privacy is not primarily an ethical question. It is a political one.

This post draws on findings from “Authoritarian Surveillance and Public Support for Digital Governance Solutions” by David Karpa and Michael Rochlitz, published in Comparative Political Studies (2025, Vol. 58, No. 10, pp. 2237-2265), and on data from Westwood & Lelkes (2024), America’s Political Pulse. For the full methodology and cross-country comparisons, see the paper.